<< Welcome || “Are You Loyal?” >>

G. Arvid Hagstrom, Bethel president from the beginning of the First World War to the beginning of the Second (1914-1941) – Bethel University Digital Library

At first glance, Bethel’s experience of World War I can seem slight. After all, with tens of thousands of books and articles written about World War I, historians may have exhausted the adjectives available to describe that conflict’s importance. Yet in the first years of the war, something so “world-changing” or “epoch-making” seems to have left few traces on a small Swedish-American high school and seminary just settling into its new home in the middle of neutral America.

Indeed, the oldest surviving comments on the war in Bethel’s historical record are frustratingly vague. In the 1915 yearbook for Bethel Academy, The Acorn, principal A.J. Wingblade observed that “It takes a good man to make a living in these war times, even if he devotes his full time to the task” — but didn’t expand on this passing remark. Bethel’s new president, G. Arvid Hagstrom, simply passed over the gloom of war: “Hope always points forward to future prospects, hence the hopeful optimistic soul always looks ahead.” As Bethel finished its first year on its new St. Paul campus, the only battlefield on Hagstrom’s mind was “the far flung battle front of foreign missionary endeavor.”1

Much of the record is simply silent. We do not know what Bethel folk thought of Woodrow Wilson’s August 1914 appeal for Americans to remain “neutral in fact, as well as in name… impartial in thought, as well as in action….”2 Nor do we know if calls for “Preparedness” in 1915-1916 or the close election of November 1916 caused as much debate on Bethel’s campus as they did elsewhere in the Union. (We do know how other Swedish-Americans responded to the war, and can perhaps draw some inferences from that history.)

Even when war came for the United States in April 1917, Bethel was less obviously touched than some of its neighboring institutions of higher learning.

University of Minnesota pharmacy students preparing digitalis for the U.S. War Department in 1918 – Courtesy of the University of Minnesota Archives, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

Not surprisingly, Minnesota’s land-grant university was affected most of all. Over 1,300 University of Minnesota students (and over two thousand alumni) enlisted, then in the fall of 1918 their places were filled by six thousand draftees enrolled in the university’s makeshift branch of the Student Army Training Corps (SATC). (It was a rough transition: courses were developed almost literally overnight, and one administrator estimated that one-third of these student-soldiers weren’t “college material.”) The university’s German department came in for investigation by the state’s overzealous Commission on Public Safety, but like most American scholars, the university’s faculty generally supported the war, with 125 serving in military or administrative capacities — including nearly five dozen professors of medicine and a dean who headed the publications division of the powerful Committee on Public Information.3 Nearly a hundred people attached to the University died in the war, yet political science professor Cephas D. Allin crowed that “We have the opportunity of a life time now to strengthen the teaching forces at the University, because the eastern institutions have been so badly hit by the war.”4

Local private colleges experienced many of the same problems, with reduced enrollment being a particular concern for smaller schools dependent on tuition. Just south of Bethel, Hamline sent nine faculty and about 350 students and alumni into the military (with five dying), and three dozen more volunteers formed an ambulance corps that served with the French Army. Further down Snelling Avenue, Macalester College had been divided by the approach of war. In February 1917, eighty-seven students praised the pro-neutrality members of Minnesota’s congressional delegation for “resisting the pressures to force the country into war,” while all but three faculty members signed a telegram to President Wilson “urging active participation in the conflict.” That dissent evaporated when Congress voted to enter the war on April 6. The college’s WWI memorial plaque names eight honored dead.5

Best prepared for the onset of war was the College of St. Thomas, a mile west of Macalester. Under the leadership of Archbishop John Ireland, the diocesan school had adopted compulsory military drill in 1903. By 1911 it was the largest private military academy in the country. In November 1916 the War Department made St. Thomas one of only six colleges in the country that could send its graduates into the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, with a senior ROTC division on campus by early 1918. All told, St. Thomas contributed sixteen faculty and over a thousand alumni (three hundred of them officers) to the military. Nineteen died in the war.6

St. Thomas cadets parading through the streets of St. Paul, Minnesota in 1917 – Courtesy of the University of St. Thomas Archives

Bethel’s experience, by contrast to that of its neighbors, seems thin, but it was not insignificant. With its seminary students exempt from military service and its academy students too young for the draft and the SATC, the brunt of Bethel’s sacrifice was born by alumni. Over eighty former students served in the military, including August Sundvall, killed in a raid near Verdun in April 1918, and Daniel Strandberg and Joel Burkman, both wounded that September. As it did for most of the four million Americans temporarily made members of the military, Armistice came before most Bethel alumni could see action. As the American Expeditionary Force assaulted German positions in early September 1918, Paul Larson was stuck in a training camp on Long Island, wishing that “I was there to help to chase that blamable Hun autocracy into the North sea.”7 When Principal Wingblade sent out a questionnaire after the war, former artilleryman Alvin Huggerth reluctantly admitted that he hadn’t arrived in France until December 1918, but insisted that “It wasn’t my fault I didn’t get across.”8 Other alumni served in non-combat roles, like naval musician Oscar Nordin, army cook Vernon Mellin, and nurses Anna Dahlby and Alice Ostergren (both of whom died while treating influenza in late 1918).

Adelphia College in Seattle, ca. 1905 – Courtesy of the Museum of History & Industry, Anders B. Wilse Collection

Bethel was on shaky financial ground in the best of times, but the economic challenges of the war made things particularly bad. In late July 1917 Pres. Hagstrom had to beg Swedish Baptist churches and other donors to fill their pledges early:

Owing to the unsettled condition of our country caused by the war, we find ourselves in the most pressing financial stringency. We have been unable to raise sufficient funds during the past year to meet the current expenses. If we are going to carry on our school work during the coming year, we must raise $5,000 before the [Swedish Baptist General] Conference meets in September.9

Similar pressures forced the closure of Adelphia College, Bethel’s sister school in Seattle, but Hagstrom’s institution survived the war — and the Academy even entered its peak period of enrollment in the 1920s.

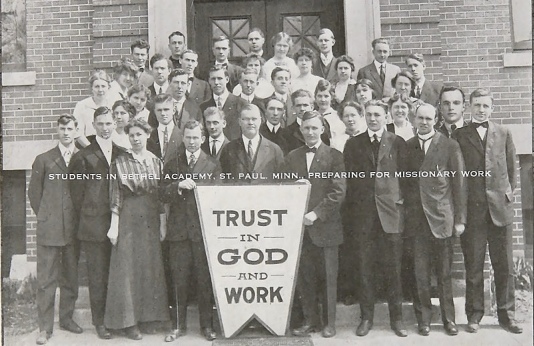

Bethel Academy students from the 1914-1915 school year, with the school motto (“Trust in God, and Work”) – Bethel University Digital Library

In the end, World War I left Bethel unchanged in important respects, such as the leadership10 and structure of the institution and its close links to Swedish Baptist churches; and the war only deepened some distinctive aspects of its culture — strong commitments to missions and personal holiness. But the war also helped hasten the assimilation of Bethel and its supporting churches into the American mainstream. It would be many years before Swedish names ceased to dominate rosters at Bethel, but in the judgment of longtime Bethel archivist and institutional historian Norris Magnuson, “The super-patriotism of the war era accelerated” the Americanization of the Swedish Baptists.11

It’s with that development that we start our story.

— Chris Gehrz

Citations

1 The [Bethel] Acorn, May 1915, pp. 8, 9.

2 Woodrow Wilson, Address to the U.S. Congress, Aug. 19, 1914.

3 James Gray, The University of Minnesota, 1851-1951 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1951), pp. 244-52; Steven J. Keillor, The Basis of Belief: A Century of Drama and Debate at the University of Minnesota (Lakeville, MN: Pogo Press, 2008), pp. 113-23.

4 Quoted in Carol S. Gruber, Mars and Minerva: World War I and the Uses of the Higher Learning in America (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1975), p. 103n.

5 Merrill E. Jarchow, Private Liberal Arts Colleges in Minnesota: Their History and Contributions (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 1973), pp. 51, 56, 91-92.

6 Ibid., p. 96.

7 Letter, Paul A. Larson to A.J. Wingblade, Sept. 1, 1918, A. J. Wingblade Papers, “Principal Academy – A.J. Wingblade – Misc. 1916-1931,” The History Center: Archives of the Baptist General Conference and Bethel University (hereafter HC).

8 Questionnaire completed by Alvin Clarence Huggerth, undated [1919], same file, HC.

9 Letter (one of many like it in this file), G. Arvid Hagstrom to C.A. Anderson, July 28, 1917, Hagstrom Papers, Box 18B, Folder 4, HC.

10 Hagstrom remained president until just before World War II, when he was succeeded by Henry Wingblade, an Academy English teacher during WWI. By that point, the Academy was closed, but A.J. Wingblade remained at Bethel as a professor.

11 Norris A. Magnuson, How We Grew: The Story of Swedish Baptists in America (Evanston, IL: Baptist General Conference, 1976).

<< Welcome || “Are You Loyal?” >>