<< Previous Essay || Conclusion >>

Like so many other aspects of the educational experience, the college curriculum was also thrown into disarray by the Sixties. Buffeted by war, protest, civil rights, feminism, and other emerging issues, curriculum often became a site of violent struggle for the soul of higher education. College and university presidents and administration represented an authoritarian power structure whose presumption of dictating what ought to be learned by students and how was egregious — or so many students argued. Indeed, some of the earliest protests of the decade came when University of California officials attempted to interfere with a student distributing materials that called for a struggle against racism at the school. Those early protests quickly coalesced around a set of propositions and accompanying solutions: the modern University had grown too large and impersonal; that impersonalized nature was largely the result of an increasingly bureaucratic management style with an expanded administration; administrators’ distance from student concerns inspired alienation, which furthered discontent with the entire system. The solution many secular student activists advocated was simple: students must gain control over the educational apparatus and control not only disciplinary policies and procedures, but also enrollment and the curriculum, opening both to underrepresented students and cultures. Students agitated to take charge of their own learning.

While Bethel’s leaders certainly made the argument that their school’s comparatively peaceful decade was due in large part to the absence of such an impersonal administrative bureaucracy, the institution was not entirely immune from student pressure on the curriculum. Beginning in January 1970, Bethel instituted a 4-1-4 calendar, opting for a three week term in January and two shorter semesters — its first calendar adjustment since switching from quarters to semesters in 1958. And starting autumn 1972, the entire curriculum was completely overhauled. With many events of the Sixties it is difficult to parse out to what degree the war specifically effected change, a fact no less true about curriculum reforms at Bethel. While other issues such as race, civil rights, and a generalised desire to ‘grapple with man’s place in modern society’ overshadowed the war in terms of class offerings under Bethel’s new curriculum, the war did appear in course catalogs beginning in 1970. To a large degree, the cumbersome process of curricular reform mitigated against the addition of war-related classes at a pace consonant with student’s desires. Accordingly, much of the Vietnam War education activity was shunted into the informal teach-in, not official catalog classes. More than the war though, Bethel’s curricular change during the Vietnam era was due to the diffused turbulence of the era, the weakening of old certainties, and the united conviction among administration, faculty, and students, that a new age called for a new learning.

❧

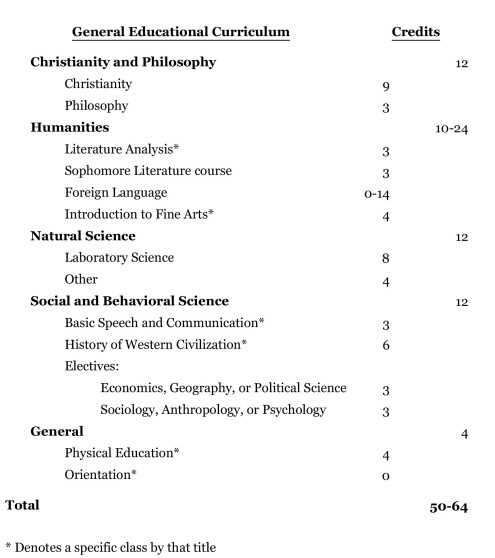

Nineteen-fifty-eight was the last year that Bethel’s curriculum underwent major revision. That year, the school switched from a quarters systems to a two semester academic year, following a number of other Minnesota private colleges.¹ The autumn semester began the first or second week of September and ran through the end of January, pausing for a two week long Christmas recess. The spring term began the first week of February and ran until June 1st. In response, the curriculum was tweaked to fit the adjusted schedule. From 1958 to 1972, Bethel’s curriculum was based on the classic liberal arts model. The school required 123 credits of its students in order to graduate, seventy-two of which were made up by the requirements of the general education program. Students were also required to complete two years of a foreign language. The general education curriculum thus took the following shape:

Within this general outline, students fit classes for their majors, and occasionally developed internships or other study experiences.

In May 1968, Clarion editor Lynn Bergfalk gave voice to what many students were feeling. “What can we do,” Bergfalk asked rhetorically, in light of the “gigantic problems that underlie the internal strife of American society?” Students were becoming increasingly aware, Bergfalk continued, of the complexity of America’s social problems and at the same time eager to engage them. Unfortunately, “neither the church nor educational institutions” had meaningfully addressed students’ desire to understand. Bergfalk explained that the biggest weakness of Bethel’s curriculum was it’s lack of classes that addressed contemporary issues. As for a place to start, Bergfalk suggested “an inter-disciplinary course dealing with the contributions of the Negro to American culture. Students could study Negro literature, discuss racial problems, and examine the social climate that induced certain attitudes or conditions.”

While both faculty and students had expressed interest in a course along these lines, Bergfalk recognized that the difficulty of adding a new course to the curriculum likely precluded flexible action. However, the administrative red tape could be bypassed, Bergfalk suggested, “if the course [were] set up on a “free university” basis.” If that could be done, perhaps the course would set the stage for a future official integration into Bethel’s catalog. “Students and faculty must provide the initiative” to make such a course reality, Bergfalk concluded.³

The “free university” Bergfalk alluded to was explained in an article accompanying the editorial. Developed out of the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley in 1964, the free university, “in its extreme form” resembled a communitarian utopia:

Curriculum is determined by consensus and the topics have ranged from the problem of God to the problem of a creative sex life to the practice of yoga. The group often invites an “expert” to join the group on an equal basis with other members. The movement has combined free thought, communal living, and a type of absolute self expression that would make John Dewey turn over in his grave.

That expression of unbridled Sixties optimism and naïveté was not what students had in mind for Bethel though. “In its milder form,” Robert Holyer wrote, “the free university has been an attempt [to] organize courses of common interest. […] While the courses are designed and initiated by students, they are taught by faculty members — often without additional remuneration. Teaching has usually avoided the classical lecture style; seminar and discussion style have proved most effective.” If the lack of payment soured professors from the work, Holyer argued that the flexible format “has enabled both faculty and students to escape the academic rut and inject an element of spontaneity and genuine interest into the educational process.”⁴ Such a system was offered by both Bergfalk and Holyer as a kind of parallel university which could improve the official course listings without needing to surmount the usual difficulties in adding additional courses.

The week after Bergfalk and Hoyler’s pieces ran, Donald Larson and David Moberg, professors of Linguistics and Sociology respectively, responded. “We commend you for pointing up the need for courses reflecting current issues and in particular for the practical suggestion of an interdisciplinary course dealing with the contributions of the Negro (and we would hope other ethnic as well as religious minorities) to American life and culture,” the pair wrote. And although they contested the notion that the curriculum contained few classes of relevance to contemporary issues, they also applauded the idea of using the free university format to enrich the curriculum.⁵ While there is no evidence students and faculty ever organized an official ‘free university’ course, the concept did manifest itself in the teach-ins held during various anti-war protest events over the next three years.

Not only were the faculty amenable to Bergfalk and Hoyler’s suggestions, they were already well aware of these concerns and had, as early as October 1967, been planning a move away from the semester calendar to a 4-1-4 format of two shorter semesters interspersed with a three week January term. Students would take four classes during each regular semester and one class during the interim, allowing for both greater focus from students, but also a greater ability on the part of the faculty to experiment pedagogically. A report from 1967 showed just how consonant faculty feeling was with student desires. Among the proposed classes for the new interim semester were:

- “Schools in the Inner City” (Education), focusing on the sociological problems of the inner city school.

- “Black Literature in the U.S.” (English), a course which would “center attention on the impressive body of literature about the racial agony of America written by those who had to live it.”

- “Ecology and Man” (Biology) which was to examine a variety of ecological and environmental problems intendent on modern civilization.

- “Understanding of Man” (Philosophy), a course with extensive readings in Huxley, Buber, Teilhard, Marx, Freud, Kierkegaard, and Niebuhr.

- “Encounter with Social Problems” (Social Sciences) which sought to expose students through first hand tours and work to the social ills of American society

- “Rhetoric of Racial Revolt” (Speech and Drama), in which students would examine “historical and contemporary black issues” through the use of “black rhetoric as the source material.”⁶

The early date of this proposal makes unclear the causes for the move toward a 4-1-4 calendar. Student pressure for new class offerings was obviously inadequate to explain the shift, even if both faculty and students agreed a new direction was needed. What is clear is that the 4-1-4 curriculum was being adopted across the country during the 1960s. In 1963, for example, Macalester and Gustavus Adolphus were among the first schools in the nation to adopt the 4-1-4 calendar.⁷ In 1970, well after the decision to adopt the new calendar had been made, the dean of the school, Virgil Olson, noted in his Annual Report to Lundquist that he had attended a 4-1-4 Conference in Chicago that year; evidently, the interim system was a popular educational innovation during the period.⁸

The practical benefits of an interim semester were significant. First, it allowed each normal semester to be shortened by a few weeks, obviating for the awkward return to campus for the final three weeks of classes in January after the Christmas break. After two weeks away from school, neither students or faculty much relished the thought to dredging up the old material for upcoming final examinations and papers. Interim allowed the autumn semester to end before Christmas. Second, the short January term allowed faculty to experiment with different pedagogical styles and design novel classes. If a professor had material that seemed significant and cohesive enough to present in class, yet could not be sustained over an entire semester, interim was the time for such teaching. The format also encouraged nontraditional forms. Roy ‘Doc’ Dalton, the Chair of History, for example, ran an interim experience called Depression House. During the month, students lived in an old farmhouse in rural Pillager Minnesota, near Brainerd. Dalton went to great lengths to recreate accurate depression conditions. Students used an outhouse, bathed and changed clothes only once per week, and brushed their teeth with baking soda.⁹

For students, interim could be a time of either intense study or relaxation, depending on whether the student took a class (students were not required to take all four interims). More importantly, interim injected some essential variety into the academic year. Even if intense, the short three week period allowed students a break from the longer-form classes they were accustomed to during the normal semesters.

❧

Bethel’s first interim took place in January 1970. Several of the proposed classes from the 1967 committee report were retained, including “Schools in the Inner City,” “Understandings of Man,” “The Student in Social Problems,” and “Rhetoric of Racial Revolt.”¹⁰ Students applauded. In the first Clarion printed after Interim 1970, the editor noted that while the change “meant intensifying course from 10 to 20 percent,” there was “little or no objection.” “Many felt January was a wasted month anyway, so little was accomplished due to Christmas vacation, exams, and semester break,” the Clarion reported. Having interviewed a number of students, the newspaper reported its findings:

Interim? I loved it! It was great! It gave me an opportunity to really enjoy going to Bethel. Only having one class enabled me to feel more relaxed. I was able to get to know the kids in my class more intimately. Some sound friendships were formed too. As for next year — I say, let’s have it again!

I thought interim was very good, and almost everybody I talked to liked it. I took the Sociology course [“The Student in Social Problems”] and the field trips were great because we were finally experiencing what we had studied. Reading about our courts can get pretty boring, but visiting a courtroom and seeit it at work, now that was something else.

My interim course was a lot of work, but I cannot say that it wasn’t worth while. I have seen more card catalogs and periodicals than I ever care to look at, yet the experience that I have behind me, I know won’t be wasted.¹¹

Bethel’s political class was equally enamoured with the new calendar. In an effusive editorial entitled “Bethel’s Curriculum Seems to be Pacing Avant-Garde Education,” Pat Faxon reviewed the many educational reforms happening across the country. Interim, she concluded, was a great success:

It offers students a chance to delve into subjects on their own which are not offered in the regular curriculum. The looser class structure allows students to experience learning through different processes, to “do their own thing” so to speak. It allows them to concentrate their interest and attention on one particular area instead of being torn in five different directions. There is more time to interact with other students — which is an important part of the learning process but is sometimes neglected during the regular semester because of studying and other pressures.¹²

Faxon was correct — interim did allow faculty to teach classes not offered as part of the regular curriculum. As such, interim was the clearest place that the Vietnam War intruded into Bethel’s curriculum. While Interim 1970 did not present any war-related classes, the next year did. In January 1971, G. William Carlson taught a class entitled “Pacifism: The Forgotten Option.” The was “designed to allow the student to develop a historical and philosophical understanding of the role of pacifism as a non-violent alternative for solving human dilemmas.” At the end of the interim, students were expected to have compose a five to seven page paper on one of two questions:

• “Your personal development of a Christian’s response to war”

• “Your personal analysis of the Christian supports for pacifism”

Each paper was presented in class and formed the basis of small group discussion.¹³ Writing in 1976, Bethel Conscientious Objector Stephen Henry credited this class for solidifying his position as a pacifist and convincing him to register as a CO.¹⁴

In 1973, Carlson taught “Radical Christianity,” a class which extended the professor’s take on anabaptist and pacifist theology into other areas of society. The course reading list suggests that class discussions delved deep into the controversies of the New Left and encouraged students to grapple with their Christian responsibilities to society.¹⁵ A year later, Carlson debuted “Utopian Political Thought,’ a course with clear connections to the Cold War context.¹⁶ These interim classes represent the clearest instance of the Vietnam War affecting Bethel’s curriculum. Although none of these three courses continued for any appreciable time under their original names, the Pacifism course from 1971 eventually morphed into “Christian Non-violence,” a course Carlson regularly taught at Bethel until his retirement in 2012, and sporadically since.

❧

In 1971, a committee of Bethel faculty unveiled a project they had worked on for years: an entirely restructured curriculum based on the new 4-1-4 calendar. G. William Carlson and Diana Magnuson argue that this revision was undertaken “in response to the increasing social and economic issues facing [the] nation and a desire by the school to address them from a Christian perspective.”¹⁷ The new curriculum landed amidst concern that the old traditional liberal arts model was inadequate to the times. Faculty documents, just as much as student writings, were shot through with a foregrounded concern for the issues of the day — everything from racism and civil rights to the war to environmentalism. But they were especially concerned with the technocratic critiques students around the country leveled at institutions of higher education: colleges were out of touch with their students, curriculum was inflexible and out of date, and the student’s ability to direct his or herself through an individualized course of study was limited. Students wanted a curriculum which was holistic, interdisciplinary, and aimed toward the development of a cohesive philosophy of human interaction with the world. It was with these considerations in mind that Bethel’s faculty redesigned the curriculum from the ground up.

The new curriculum was idealistic in the extreme. Nearly every accepted category and term was jettisoned as the faculty strove to capture the heady notion that everything could be re-negotiated in this decade of change. That spirit was reflected even in the physical design of the catalogs. Since the first decade of the twentieth century, Bethel had released a yearly catalog stipulating policies, regulations, the calendar, and in varying level of detail, graduation requirements and class listings. Each catalog represented a single academic year and was published in a standard five-by-eight inch portrait format. Starting in 1970-71, these conventions flew out the window. Suddenly, the course listings were divorced from the policy catalog; an “admissions” catalog appeared as well. The format changed too, shifting to a landscape layout and featuring artwork increasingly redolent of its decade of origin. Even the notion that each catalog corresponded to a single academic year disappeared; two year spans became the new norm under the revised curriculum.

Even as terminology and artwork were caught up in the countercultural whirlwind of the Sixties, the curriculum remained rooted in the liberal arts. Indeed, president Lundquist made special note of this fact in announcing the new curriculum in the 1972 Annual Report: “the primary focus, however, is upon the liberal arts, with its emphasis upon the development of the whole man.”¹⁸ The liberal arts, Lundquist asserted, were under continual attack from those who had only pragmatic and utilitarian concern. Through the rest of the Report, Lundquist defended the liberal arts as practiced at Bethel.

That language is strikingly different than the tone Lundquist employed in his Annual Reports to the Conference from 1965 through 1971 — enough to merit a digression. In the late 1950s through the 1963 Annual Report, Lundquist’s tone is perfunctory, writing in a manner similar to a public accountant. After reciting enrollment figures, Lundquist typically proceeded to any notable challenges or successes of the prior year, then ended with a note on finances and segued into the financial statements. In 1965, that changed. Gone was the dispassionate reporting, replaced by an earnest and learned attempt to establish “The Christian Idea of Bethel.”¹⁹ In the previous year, the Conference had voted to deny Bethel funding under Lyndon Johnson’s new scheme which made federal monies available to colleges for building programs. As Bethel was in the midst of a building program on its new Arden Hills campus, this money would have been a boon. Yet the Conference wavered, citing concerns about federal intervention at the school. That decision reflected doubts that had festered in the Conference for years that Bethel was no longer a needed enterprise. In the post-war growth, Bethel’s funding needs had rapidly expanded, putting a greater strain on the Conference. At the same time, the original purposes for Bethel — first as a training school for Swedish-speaking ministers, then as an acculturating institution for Swedish Baptist youth — had dissipated. Bethel students themselves were no longer Swedish-speakers, nor were their parents. As other evangelical schools existed, the question of Bethel’s continued operation arose. Indeed, that existential questioning extended to the faculty, with some in 1966 and 1967 wondering whether Bethel should be “scraped.”²⁰

Those were questions Lundquist was eager to quash. Starting in 1965, Lundquist set out to chart a new course in light of the school’s changed purpose, articulating a new vision for Bethel as an institution of Christian higher education. He could no longer rely on ethnic loyalty to support the school in an increasingly Americanized and diverse denomination. What was needed was a new vision, one which would set Bethel apart even from its competitor evangelical schools like Wheaton and Calvin. The 1965-1971 Annual Reports are testaments to Lundquist’s vision. In them, he aggressively reasserted Bethel’s historic pietist impulses and irenicism, setting them up as distinctives which could shape the school’s culture and educational philosophy. Central to this task were the liberal arts.

The strategy solidified support from the Conference. Most importantly, the College’s relocation to the Arden Hills campus proceeded in the autumn of 1972. With that accomplished, the tension in Lundquist’s Annual Reports slackened; having moved to a new multi-million dollar location, he could be sure that Bethel was supported. The time to pull the plug on the school was in the mid 1960s, before the move. Accordingly, in the early 1970s, Lundquist could ease back from his energetic defense of the school.

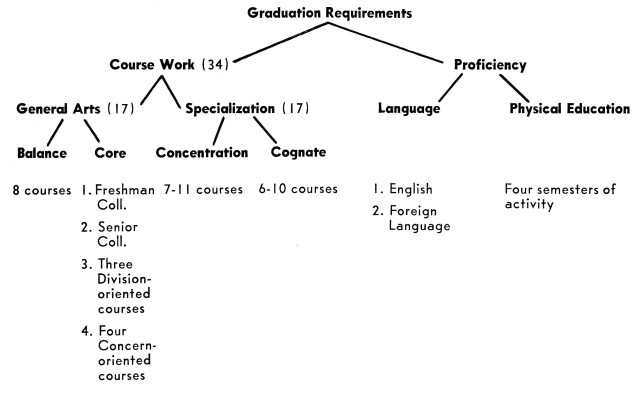

The new curriculum embodied the upheaval of conventions so characteristic of the decade in which it was conceived. Instead of a credit-based system, the new curriculum established courses — thirty-four of them — as the new metric for graduation. Majors turned into specializations, minors became cognates. The departmental system was retained at the organizational level, but for academic purposes, each department was grouped into one of four Divisions: Humanities, Arts and Letters, Behavioural Sciences, and Natural Sciences. On the student side, four Concerns were established: Orientation, Communication, Environment, and Creativity. The general education curriculum now consisted of two broad divisions: General Arts, comprising the Balance and the Core, and Proficiency, comprising Language and Physical Education.

Within the Core of the General Arts, all students enrolled in Freshman Colloquy during their first year and Senior Colloquy during their final year. Between those two courses were three division courses — one from each division other than the student’s specialization — and one of each of the concern courses. Eight additional electives comprised the balance of the General Arts requirements.²¹ The new curriculum thus took the following shape:

When announced in November 1971, the student body’s reaction was mixed. Much controversy surrounded two questions in particular: how would the new requirements apply to existing students, and what of the proposed foreign language proficiency requirement? While the Clarion published a number of pieces examining these problems in depth — as well as faculty responses — Marjorie Rusche came out in favour of the new curriculum, arguing that its basic structure was sound. Still, departmental jealousies and structural pressures were mitigating against the curriculum achieving the student-directed flexibility it sought to achieve. It was natural, Rusche argued, for faculty to press for their own courses to be included among the general education requirements — reduced enrollment could lead to department cuts, after all. Yet the result was to undercut the very purpose of the new curriculum.²²

❧

The new curriculum was deployed beginning in the autumn of 1972, the same semester college students first stepped foot on the new Arden Hills campus. The new system lasted until 1985 when it was revised to its current format. From the beginning, the changes appeared too drastic. Eliminating credits in favor of courses made the system unwieldy, and the the intentionally fuzzy-edged interdisciplinary Division and Concern categories became hard to define and sustain.²³ In hindsight, the new curriculum was clearly a product of the idealistic near-hubris the Sixties bred so well. By 1985, faculty reflected on the lesson that not everything need be reinvented. Accordingly, the physical design of Bethel’s catalogs returned to a more conventional form, resuming by 1981 the traditional format.

Yet, the fifteen years under the new curriculum did establish a number of important Bethel institutions which remain to the present. The Freshman Colloquy was the direct ancestor of the contemporary Introduction to the Liberal Arts. Likewise, the Senior Colloquy survived to become today’s Senior Capstone (P) course. And several aspects from the older 1958–1971 curriculum were recovered in 1985, including Introduction to Fine Arts — today’s Introduction to Creative Arts.

In all, the Vietnam War had a limited effect on curricular reform at Bethel College, an effort that would have likely proceeded without the war. Aside from several interim classes, all taught by G. William Carlson, it does not appear that the war significantly impacted the formal curriculum, even in an age of change. The war did, however, manifest itself in informal teach-ins in 1969, 1970, and 1971 — teach-ins which followed the model of the “free university” established at Berkeley in 1964. More important than the war for the curriculum were societal racism and civil rights. When students pushed in 1968 for expanded class offerings, it was these subjects that they turned to, not the war. Yet it is far from clear that student pressures actually accomplished anything of substance; the one incidence of student discontent with class offerings took place after the faculty had been working for over a year to implement interim and expand contemporary classes. Curricular reform was thus the rare subject during the Vietnam era on which students, faculty, and administration largely agreed. Working together, the three groups managed to produced a radical new curriculum that was both a reflection and examination of its era. But as the ethos of the Sixties faded away in the next decade, so did the concerns which animated the reformed curriculum. The ‘revolutionary’ new curriculum quickly became a relic of an earlier era’s excesses, and was duly replaced.

— Fletcher Warren

<< Previous Essay || Conclusion >>

Citations

¹ Merrill Jarchow, Private Liberal Arts Colleges in Minnesota (Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1973), 55, 73, 84, 124, 169, 173.

² William Carlson and Dianna Magnuson, “Bethel College and Seminary on the Move,” in Five Decades of Growth and Change: The Baptist General Conference and Bethel College and Seminary 1952-2002 edited by James and Carole Spickelmier (Minneapolis: The History Center, 2003), 34; G. William Carlson and Dianna Magnuson, Persevere, Läsare, and Clarion (Saint Paul: Bethel University, 1997), 48; Academic Catalog, 1968-69, 38-9.

³ Lynn Bergfalk, “Students Need Courses Reflecting Current Issues,” The Clarion 1968-05-02.

⁴ Robert Hoyler, “Current Free University Movement Challenges Weak Points of Curriculum,” The Clarion 1968-05-02.

⁵ Donald Larson and David Moberg, “Professors Examine Course Proposal,” The Clarion 1968-05-10.

⁶ Interim Term Committee Report, October 16, 1969, Minutes, Reports, and Notices of the College Faculty, 1965-1970, The History Center: Archives of the Baptist General Conference and Bethel University (hereafter HC).

⁷ Jarchow, Private Liberal Arts Colleges, 150.

⁸ Virgil Olson, Dean’s Annual Report to the President, 1970, Reports to the President 1969-70, Box 39, Lundquist Presidential Papers, HC.

⁹ Carlson and Magnuson, Persevere, Läsere, and Clarion, 49.

¹⁰ Report of the Interim Term Committee to the Faculty, October 2, 1969, Minutes, Reports, and Notices of the College Faculty, 1965-1970, The History Center: Archives of the Baptist General Conference and Bethel University (hereafter HC).

¹¹ “Interim ‘70 Stimulates Interaction,” The Clarion 1970-02-06.

¹² Pat Faxon, “Bethel’s Curriculum Seems to be Pacing Avant-Garde Education,” The Clarion 1970-02-06.

¹³ Syllabus for “Pacifism: The Forgotten Option,” Interim 1971, Personal Collection of G. William Carlson (hereafter GWC).

¹⁴ Stephen Henry, “Questionnaire,” Responses to 1976 Cedric Broughton survey, GWC.

¹⁵ Syllabus for “Radical Christianity,” 1973, GWC.

¹⁶ Syllabus for “Utopian Political Thought,” 1974, GWC.

¹⁷ Carlson and Magnuson, “Bethel on the Move,” 34.

¹⁸ Carl Lundquist, “Annual Report to the Conference,” 1971, Reports to the President 1971-72, Box 39, Lundquist Presidential Papers, HC.

¹⁹ Carl Lundquist, “Annual Report of the President,” Report of the Board of Education, In 1965 Annual of the Baptist General Conference, 117.

²⁰ “Let’s Scrap Bethel,” Bethel Faculty Journal 1966-05-31; “Let’s Not Scrap Bethel,” Bethel Faculty Journal 1967-03-01.

²¹ Academic Catalog, 1971-72 — Registration, Bethel College, 6-9.

²² Marjorie Rusche, “New Curriculum Being Subverted by Departmental Self-Interest,” The Clarion 1970-11-20.

²³ Carlson and Magnuson, “Bethel College on the Move,” 34.