<< “Are You Loyal?” || Suffering Loss, Making Meaning >>

“Shall it be held lawful to make an occupation of the sword, when the Lord proclaims that he who uses the sword shall perish by the sword? And shall the son of peace take part in the battle when it does not become him even to sue at law?… Nowhere does the Christian change his character. — Tertullian, AD 2111

❧

Throughout church history Christians have wrestled with whether and how they ought to participate in warfare. Overwhelmingly, most people in the history of Bethel and its denomination have disagreed with the radical pacifism of Tertullian and followed the counsel of Ambrose, Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, and others: that Christians might, regrettably and only after strict criteria are met, take life as combatants. But even in “just wars,” the people of our study struggled mightily with another of Tertullian’s concerns: Can one live a distinctively Christian life within the military?

Early in the third century, that great African apologist was concerned that participation in the military of the Roman Empire required Christian participation in pagan religious rituals. In the first half of the twentieth century, Swedish-American Baptists feared that participation in the military of the United States put followers of Jesus in the path of other kinds of moral hazards.

“An army is no school of morals,” Bethel president Henry Wingblade observed in January 1942. “It never was. There will be no end of debasing influences brought to bear on our boys in camp.”2 In June 1943, delegates from Michigan urged that the Swedish Baptist General Conference (BGC) pay greater attention to the care of servicemen, who were “subjected to conditions which are not conducive to spiritual growth and moral stability.”3 From basic training, one recruit warned his former classmates at Bethel: “Those of you who will not get into this will never know what a test it is—these men live such un-Christian lives.”4 Similar concerns had been expressed in the First World War as well.

We’ll come to the “trials and temptations” specific to military service shortly, but first, we need some religious context. Thanks to their dual Baptist and Pietist heritage, the people of the Swedish Baptist General Conference placed particular emphasis on the need for converted Christians to lead lives of personal holiness. For example, in a discussion of sanctification, Bethel founder John Alexis Edgren concluded that, “No one will be finally saved who has not kept faith and earnestly striven for holiness. All true children of God do that.” Without singling out any vice in particular, Edgren did emphasize that the “church should be made up out of true Christians” and “should also keep watch on members whose lives do not correspond to their profession, and withdraw from them and exclude them from their fellowship.”5

Neither the experience of two world wars nor the dropping of “Swedish” from their denomination’s name changed most Conference Baptists’ belief that the true church was a voluntary gathering of visibly regenerate converts living holy, disciplined lives. It was a conviction the leaders of Bethel clung to as well. In his oft-reprinted book My Church, longtime Bethel Seminary dean Gordon Johnson wrote:

The New Testament Christian was marked by a life distinct from that of others about him. Certainly those in the modern church also ought to be marked by a distinct life because they belong to God. One source of weakness in the church is the unchrist-like lives of its members. The strength of the church must be guarded by constantly emphasizing purity of life. If the church is too tolerant in the matter of Christian living, decay will go on until the church will not tolerate a ministry that preaches the complete gospel—the gospel that deals in sin.6

Edgren’s longest-serving (1954-1982) successor as Bethel president, Carl Lundquist, believed that the college was obliged to train its students in “the distinctive Christian life as one of voluntary self-discipline.”7

Among other worldly behaviors, Lundquist particularly warned against premarital sex and the consumption of alcohol, the two practices that Conference Baptists in both world wars had viewed as the greatest threats to the moral welfare of their young men and women in the military.

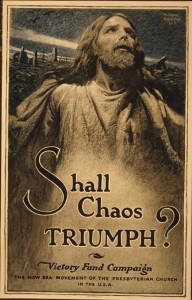

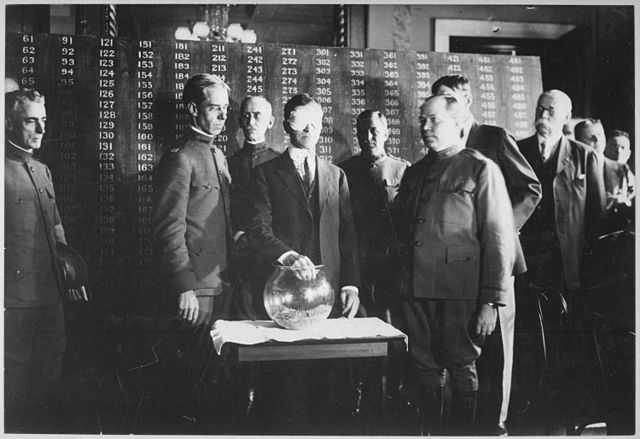

Secretary of War Newton Baker drawing the first number in the July 1917 draft lottery – U.S. National Archives

“Military service was notoriously associated with dissolute behavior,” writes Robert Zieger in his history of the American experience of World War I. “Soldiers were legendary fornicators, drinkers, blasphemers, and general hell raisers. Communities adjacent to military posts were almost by definition sites of saloons, gambling dens, and brothels.”8

Into such an atmosphere, the United States was to send four million young men “[b]rimming with eagerness and enthusiasm” and possessed of a “keen sense of schoolboyish anticipation and excitement,” in the words of historian David Kennedy. Perhaps making the problem worse, Secretary of War Newton Baker “consciously strove to model training camps on ‘the analogy of the American college,’” with one trainee describing Illinois’ Fort Sheridan (where the ill-fated Bethel alum August Sundvall trained) as being like a “college campus on the eve of a big game.” So, writes Kennedy, “[e]ven more than college boys, the young men in the Army were to be protected from wickedness and vice.”9

The European experience suggested that sexual vices were of especially pressing concern. Though it was understandably overshadowed by losses on the Western Front, France suffered an epidemic of sexually transmitted diseases in the first eighteen months of the war, with the number of syphilis cases rising a total of 50% over prewar levels. On the home front that figure rose by two-thirds, as infected soldiers on leave spread the disease to their wives and other sexual partners. The French government responded by tightening the regulation of state-sponsored brothels, a solution that the U.S. government quickly declined when their Gallic allies offered to make such maisons tolerées available to doughboys in early 1918. Instead, the Wilson Administration had taken a more puritanical tack, passing a law in May 1917 that created prostitution-free zones around military bases.

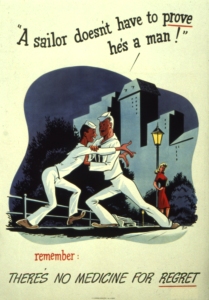

The campaign to limit the spread of STDs in the military was revived during World War II, as seen in this 1942 poster (a relatively subtle example of the genre) – U.S. National Library of Medicine

Dismayed by the behavior of American soldiers campaigning in Mexico in 1916 with “a good deal of time hanging rather heavily on their hands,” Secretary of War Baker had already decided that the American Expeditionary Force ought to “be a virtuous, democratic army, different in recruitment, composition, and most importantly, moral stature from any previous army.”10 American churches and parachurch organizations like the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) were enlisted as partners in the cause. Coordinating the moral reform effort was the Commission on Training Camp Activities (CTCA), a military-sanctioned private group headed by philanthropist Raymond Fosdick, brother of the great liberal pastor Harry Emerson Fosdick. “A German Bullet is Cleaner than a Whore,” warned one CTCA poster common in Army camps. “A Soldier who gets a dose [of venereal disease] is a Traitor!”, announced another. Hand in hand with military intelligence officers and local law enforcement officials, the CTCA investigated saloons and brothels. “In community after community,” observes Zieger, “this combination of moral outrage, patriotic sentiment, and federal power closed down saloons, scattered prostitutes, and created a cordon of vicelessness around army posts.”11

Its 1918 “war resolution” made clear that Bethel’s denomination was wholly sympathetic to the CTCA’s aims. After pledging “allegiance to the President and government of the United States” and affirming “loyalty to those principles for which our country and our noble allies stand,” delegates reserved an “especially” clause to underscore their “support of the measures for national prohibition and for those agencies and organizations which promote the moral and spiritual welfare of our military and naval forces.”12

“…imagine Ned Flanders of The Simpsons, but older and shorter, and carrying on his slight frame a suit, a waistcoat, and, his followers believed, the fate of the Republic,” suggests Okrent of Wheeler – Library of Congress

The reference to “national prohibition” is especially noteworthy, coming in the year that the Eighteenth Amendment began to be ratified by state legislatures. The notion that the prohibition of alcohol was a colossal failure has become such a commonplace that we need to work to remember just how powerful the temperance movement was in the early 20th century. The war did much to boost the cause of the Anti-Saloon League (ASL), helping to make it “the mightiest pressure group in the nation’s history” in the judgment of writer Daniel Okrent. Led by the tireless, ruthless Wayne B. Wheeler, the ASL enjoyed the support — and influenced the voting patterns — of millions of churchgoing Americans.13

That includes most of the members of Bethel’s denomination. At the 1917 meeting of the Swedish Baptist General Conference, delegates resolved to “urgently implore our churches and individual members to vigilantly stay in the fight and to co-operate with the Anti-Saloon League and work hand in hand with all sane temperance forces so as to maintain our captured trenches and make our positions secure and our ultimate goal—a saloon-less and temperate nation—a question of only a very short time.”14

The use of Western Front language (“captured trenches”) underscores the hopes of temperance advocates in 1917: that World War I would hasten the prohibition of alcohol. They employed an array of arguments, none more effective than when they questioned the patriotism of the largely German-American brewers. In one February 1918 attack, the “dry” lieutenant governor of Wisconsin didn’t hesitate to name some of Milwaukee’s most famous employers:

We have German enemies across the water. We have German enemies in this country too. And the worst of all our German enemies, the most treacherous, the most menacing, are Pabst, Schlitz, Blatz, and Miller.15

“Save wine for our soldiers”: the French and American governments took very different attitudes towards regulating their soldiers’ lifestyles – University of Illinois Library

Later in 1918, Disciples of Christ minister Alva Taylor urged fellow temperance advocates to take advantage of the war and “organize the world for the final battle on Kaiser Alcohol; let us bury the two Kaisers in the same grave.” Taylor took heart from widely publicized comments from Gen. John J. Pershing, the senior American military commander in Europe:

Banish the entire liquor industry from the United States; close every saloon, every brewery; suppress drinking by severe punishment to the drinker, and if necessary by death to the seller, or the maker, or both as traitors, and the nation will suddenly find itself amazed at its efficiency and startled at the increase of its labor supply. I shall not go slow on prohibition, for I know what is the greatest foe to my men, greater even than the bullets of the enemy.16

Indeed, the government progressively eliminated (“for the duration” of the war, at least) the sale of alcohol to soldiers, the importation and then production of spirits, and the sale of liquor within five miles of naval bases. Years before he became the last American president to support Prohibition, Herbert Hoover used the power of the new U.S. Food Administration to slash the amount of grain available to brewers by 30%.17 Even this was not enough for the BGC, whose delegates complained that “our government did not find it expedient to prohibit the whole traffic in liquor during the progress of this war.”18

The public side of this partnership was motivated by pragmatism (militaries on each side of WWI feared that STDs would reduce the number of “effectives” available for combat) and, among Progressives like Baker and Fosdick, a desire to use the war as a massive experiment in social engineering.19 But for pietistic Swedish Baptists, having sex outside of marriage and getting drunk had implications more significant than reduced military efficiency. Not just civic virtue, but one’s sanctification was at stake.

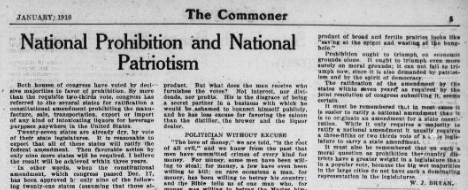

“So much greater is their passion for dollars than their patriotism that [those engaged in the liquor traffic] would, if they could, make drunkards of the entire army, and leave us defenseless before a foreign foe.” William Jennings Bryan argues for the 18th Amendment in a Lincoln, Nebraska newspaper on New Year’s Day, 1918 – Chronicling America, Library of Congress

to express its joy and satisfaction for the permanent elimination of the curse of drink, and to recommend to all our churches and people a continued loyal support of the Anti-Saloon League, the organization that has been the dominating factor toward the happy solution of this issue, and especially to the League’s endeavor to secure enforcement legislation sure and permanent, and to insure the strictest enforcement of the Eighteenth amendment. We warn our people to be on guard, lest in the last minute some fruits of the victory be lost. We therefore urge our people to co-operate with every agency and movement for the enforcement of prohibition.20

Swedish-American Baptists lamented that their homeland did not embrace temperance. This prohibition poster supported the losing side in a 1922 referendum – Royal Swedish Library

Strong opposition to “King [formerly, Kaiser] Alcohol” continued to prevail at the Swedish Baptists’ educational institutions. Bethel president G. Arvid Hagstrom was a staunch advocate of Prohibition. When a new restaurant opened just down the street from the campus, Bethel Academy principal A.J. Wingblade spied on the establishment and reported back to Hagstrom that it was a “speakeasy.”21 Before coming to America, Bethel Seminary dean Carl Lagergren had edited a temperance newsletter in Sweden and run for the Riksdag as a prohibitionist.22 As repeal of Prohibition was debated in 1932, Bethel hosted “dry” speakers like a local businessman whose chapel talk, claimed The Clarion, “knocked down prop after prop of the wet’s arguments.”23

Nevertheless, the “wets” won the day, as the enforcement of Prohibition both reduced alcohol consumption and greatly boosted criminal activity. Only five states had ratified the Twenty-First Amendment when the BGC met in June 1933, but no one was so dry as to ignore the “evident sentiment in favor” of repeal.24 Prohibition was dead by the time the denomination met again a year later, causing delegates to decry how their “young people are constantly tempted by the open sale and clever advertisement of liquor.”25

So when an English-language BGC periodical finally took notice of the start of the Second World War, in November 1939, Our Youth columnist Haddon Klingberg took a surprising tack, fretting that there “is a greater problem for us than an European or even a World War. But we are so intent on studying the movements of men and events three thousand miles away that we fail to see what goes on about us….” What problem could have been greater than the onset of WWII?

On my desk, is a paragraph which reads: “In the United States, there are today engaged in the manufacture and sale of beverage alcohol more women and girls than we had men in the world war.”26

Though he joined other BGC leaders in his support for neutrality, Klingberg could see one potentially positive result of American involvement: “Though we shudder to think of unfurling the Stars and Stripes on another battle field, perhaps war would return us to sane deliberation of” the problem of alcohol. And then he quoted Pershing’s support for prohibition: “…for I know what is the greatest foe to my men, greater even than the bullets of the enemy.”

Indeed, once the U.S. did join the war, writers in The [BGC] Standard hoped to see a revival of the 1917-1918 public-private partnership against King Alcohol. A. J. Wingblade (now a professor in the junior college, following the 1936 closure of the Academy) celebrated that March 8, 1942 would mark Temperance Sunday on Bethel’s campus: “Someone calls liquor our fourth enemy,” claimed Wingblade, “aligning it with Germany, Italy, and Japan.”27 Mrs. Marshall Carlson of Chicago called on her “Women’s Corner” readers to urge their legislators and the Roosevelt Administration to revive the WWI-era regulations that restricted access to alcohol on and near military bases:

Our Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, stated recently that it would be unfair to deprive the soldier of the privileges enjoyed by civilians. Every soldier is denied the privilege of going to bed when he wants to; he gets up when the bugle blows, or else–, he eats what is set before him, he wears clothes issued to him, lives where he is told, goes in and out when given permission, and yet must not be denied the privilege of drinking what will distort his vision, dull his hearing, unsteady his nerves, delay his muscular reactions, generally lower his moral character and limit his usual activities.28

Standard editors J.O. Backlund and C. George Ericson joined the crusade with an Easter editorial concluding that it was likely that the nation would return to the “War Prohibition” of 1917-1918, “when even millions of wets had to concede its necessity because all possible food had to be conserved to feed millions of starving people in Europe, and to feed two million American soldiers sent abroad.”29

But just a few weeks later, when it became clear that the government would not in fact revive the prohibitionist regulations of WWI, the Standard‘s editors professed themselves unconvinced by the War Department’s arguments:

The way to meet the crisis, according to some, is to declare a devil’s Sunday and place the common ideals of civilized nations in suspension.

War is a time when things of that sort may be proposed freely—though they may possibly be practiced on the quiet during ordinary times. Because we live in unusual times we are supposed to be freed from the inhibitions of ordinary tenets of morality

…The answer has been that we should not deprive the boys of any joys that they might find in their drab and cheerless camp life. In other words, let them sin. Let the Decalgue [sic] be suspended for the duration.30

— Chris Gehrz

Citations

1 Tertullian, “The Chaplet,” in Latin Christianity: Its Founder, Tertullian, ed. and trans. Philip Schaff, The Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. III. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1978), p. 99.

2 The [BGC] Standard, Jan. 10, 1942

3 1943 report of the Executive Committee, 1943-1944 Annual Report of the Swedish Baptist Churches of America, Part I, p. 12.

4 The Bethel Clarion, Mar. 31, 1943.

5 John Alexis Edgren, Biblisk Troslära (1890); translated by J. O. Backlund as Fundamentals of Faith (Chicago: Baptist Conference Press, 1948), pp. 152, 163.

6 Gordon G. Johnson, My Church, rev. ed. (Arlington Heights, IL: Harvest, 1994), p. 54.

7 Carl H. Lundquist, “The Christian Idea of Bethel,” 1965 Annual Report of the Baptist General Conference, p. 128. The other “social practices” on Lundquist’s list — tobacco use, social dancing, and “indiscriminate participation” in movie- and playgoing — were also prevalent on and near military bases, of course.

8 Robert H. Zieger, America’s Great War: World War I and the American Experience (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000), p. 89.

9 David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980), p. 185.

10 Zieger, America’s Great War, p. 89.

11 Ibid., p. 90.

12 “War Resolution,” Årsbok – Svenska Baptistförsamlingarna inom Amerika, 1917-1918, p. 17. (In a yearbook that’s primarily written in Swedish, this resolution is in English.)

13 Daniel Okrent, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (New York: Scribner, 2010), pp. 2, 38.

14 Temperance resolution, Årsbok – Svenska Baptistförsamlingarna inom Amerika, 1916-1917, pp. 69-70. (Here again, this particular resolution was in English.)

15 Quoted in Okrent, Last Call, p. 100.

16 Alva W. Taylor, “General Pershing an Advocate of Prohibition,” The Christian Century, Sept. 12, 1918.

17 The U.S. government was not alone in taking such steps. The British government had earlier established a Central Control Board to regulate consumption and production of alcohol; see Robert Duncan, Pubs and Patriots: The Drink Crisis in Britain during World War I (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013).

18 Årsbok, 1916-1917, p. 69.

19 See Nancy K. Bristow, Making Men Moral: Social Engineering during the Great War (New York: NYU Press, 1996), especially ch. 4.

20 Temperance resolution, Årsbok – Svenska Baptistförsamlingarna inom Amerika, 1918-1919, pp. 85-86.

21 G. William Carlson and Diana L. Magnuson, Persevere, Läsare, and Clarion: Celebrating Bethel’s 125th Anniversary (St. Paul: Bethel College and Seminary, 1997), p. 35.

22 History of the Swedes of Illinois, Part I, ed. Ernst W. Olson (Chicago: Engberg-Holmberg, 1908), pp. 358-59.

23 The Bethel Clarion, Nov. 5, 1932.

24 “Temperance and Prohibition,” 1933-1934 Annual Report of the Swedish Baptist Churches of America, Part I, p. 101.

25 “Temperance Education,” 1934-1935 Annual Report of the Swedish Baptist Churches of America, Part I, p. 126.

26 Haddon E. Klingberg, “Warfare Abroad—And at Home,” Our Youth, Nov. 5, 1939. Klingberg, incidentally, was the son of John Eric Klingberg, founder of one of the most important Swedish Baptist institutions, the Klingberg Children’s Home, which Haddon took over on his father’s death in 1946.

27 The Standard, Feb. 28, 1942.

28 The Standard, Mar. 21, 1942. Six weeks later Mrs. Carlson claimed that an effort was underway to conceal the fact “That a large contributing cause for the Pearl Harbor disaster was the customary Saturday night drinking of intoxicants in Honolulu”; The Standard, May 2, 1942. A month later, a Baptist missionary alleged that “prior to the bombing, Japanese brought in unusually large quantities of liquors to sell our men…. Many, if not most of the dealers in intoxicants are Japanese”; The Standard, June 13, 1942.

29 The Standard, Apr. 4, 1942.

30 The Standard, May 16, 1942.